|

By Greg Hupé

(Meteorite Magazine, August 2003)

|

|

One day the telephone rang and the voice on the other end said, “Hello, my name is Dave and I have

read about Adam’s and your many successful expeditions throughout the world. I have an ideal

location in mind and want to know if you would like to mount a meteorite expedition to Kenya.”

Always looking for new opportunities, Adam and I quickly agreed that we would like to participate.

Knowing about the dangers of central Africa, I asked if he had any objections if I invited our

friend, Allan, so we would have safety in numbers. He agreed and we started the planning process,

which would take several months.

The time spent prior to the start of the expedition was used to study satellite and topographical

maps, and corresponding with missionaries to determine the most promising locations to search.

Dave and I exchanged many emails and phone conversations as part of the process. Allan decided

that the trip would be worthwhile because he had never been there before. Any meteorites we found

would be icing on the cake. Our main goals were to search the regions we thought most likely to

have extra terrestrial material and to educate the indigenous people to look for meteorites in

order to supplement their meager incomes.

Another consideration we had prior to leaving was for our safety. We looked into hiring armed

“assistants” that would provide protection for us during our journey into the northern parts of

Kenya. This region borders Somalia where armed bandits, poachers and ethnic extremist’s roam

freely to instill terror and commit piracy at will. We did not want to take any chances.

This pioneering expedition almost never took place due to the forthcoming Iraqi war and our

ailing mother’s “touch and go” condition. She had been fighting cancer for 10 months so I was

willing to cancel the trip up to the last minute if her health showed any signs of deteriorating.

My brother, Adam, reassured me that he would remain behind and take good care of her, so I

departed for New York on February 23, 2003 to meet our East Coast team members. Each expedition

Adam and I participate in usually consists of different partners due to location, schedules,

personalities and the fact that we like to give others the opportunity to join us.

We found ourselves in Nairobi, with guarded anticipation for the start of our nearly three week

excursion. Settling in after many hours of sleepless travel, we met with our Kenyan partners.

Here we determined how much water, food, fuel and emergency supplies we would need for the

journey. Our Master Guide’s name was Mwaura. He was a muscular Samburu tribesman but very soft

spoken and mellow. He had the look and demeanor that nothing could make him worry. He took

charge of the meeting and advised us on what locations he thought would best match our

requirements. His firsthand experience would prove priceless throughout our travels. The cook

for the expedition was named Chep, from the Kikuyu tribe. He preferred to be called the

“Camp Master” and was a small man with a huge amount of energy. Whenever we would stop for a

break or for the night, he would tirelessly prepare food to make sure we were all well fed.

Our Guide Assistant was another Kenyan named Sammy who ended up being more of an extra body

than anything else. He never seemed to help with anything and appeared to just eat and sleep.

He was more interested in flirting

|

with our translator, April, who was an American girl. She

was a “natural” sort who liked to spit and had a foul mouth. Towards the end of the expedition

she was swearing worse than any biker!

I would describe myself as a cross between Mwaura and Chep. I like to kick back and relax but

most often am itching to get onto the next task at hand. We nicknamed Dave “Gadget-Guy Dave”,

as he had a device or contraption for every occasion, whether it was for our amusement or

safety. He is a hardy type with an inquisitive attitude. Allan is very laid back and has a

gruff New York accent when he speaks that makes one feel he is always upset, but the opposite

is true. He wasn’t taking any chances with the local food so

|

|

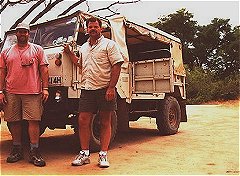

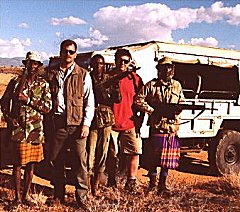

Dave and Greg with military transport.

|

|

he brought his own prepackaged

chicken and tuna fish. On some days this would become a godsend, as we didn’t know what kind

of wild game Chep had prepared for us.

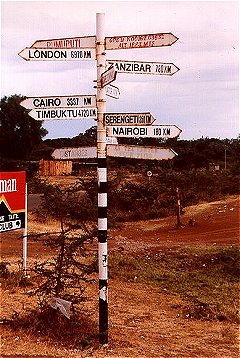

The next morning everyone assembled in the hotel parking

|

|

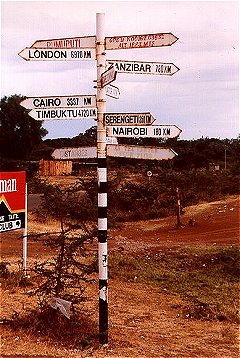

The sign to Rumuruti and beyond...

|

|

lot. Our mode of transportation was

an old military Land Rover previously used to transport troops and anti-aircraft guns. We

loaded our equipment and rations then headed north into Samburu territory towards Rumuruti,

a village where the 1934 witnessed fall of the famous R chondrite meteorite landed.

“…the natives are getting restless!”

After we left Rumuruti, the road became an unpaved trail full of giant potholes that would

rattle us to the core and would continue this way for the majority of the trip. Several

hours after dark we arrived at our destination, a secure encampment in the Samburu village

of Maralal. We set up camp and Chep cooked a well-needed meal. An hour later we heard several

family groups in the distance start to sing and play drums. It was a pleasant but almost

eerie sensation. Allan exclaimed, “Now I can truly say the natives are getting restless!”

One of the devices Dave brought with him on the trip was a satellite phone, which proved

more frustrating than it was worth. You would have to be in a clearing for the phone to

pick up a satellite and even then, the chances were

remote at best. I made the first of many calls throughout the trip to my brother who would

give me daily updates about our mother’s health. He said she

|

|

looked good and was resting comfortably at home.

Morning came upon us quickly as we readied ourselves in the pre-dawn darkness. It took a

couple of hours to pull up camp and embark on our day’s travels. Eventually we made our

way to the large village of Baragoi where we planted the seed of meteorite awareness by

showing the tribal

|

|

members actual material and handing out magnets. We drove through and, after rounding a curve in the trail, we came face to face with a van

full of armed militants, several of whom were outside the vehicle holding their fully

automatic weapons. We thought that it was an ambush and expected to be attacked!

“You’re going to war?!”

After several minutes of discussion between our guide and the leader, another fighter asked

something in broken English. Allan exclaimed, “You’re going to war?!” Our translator said,

“No, they ask if we want four.” As it turned out, we did not know these were our armed

“assistants” to the northern region. We only had room for three so we picked the toughest

looking men

|

|

Greg and Dave with armed escorts.

|

|

and headed into the danger zone. We were now armed to the

teeth! Allan and I would constantly have to push their machine guns away because they kept

letting them drift towards us. We thought that we would get our heads blown

|

|

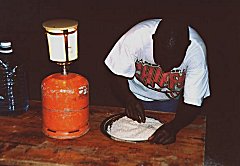

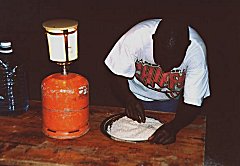

Chep ‘counting’ the rice for dinner.

|

|

off at the next bump in the road.

We made our final stop for the day; a primitive village called South Horr. Meanwhile, Chep

busied himself with preparing dinner. We noticed he was shuffling through a plate of rice

so we asked what he was doing. His reply was, “I am counting the rice.” We would later find

out he was removing bugs that had made their way into the food supplies. We were too tired

and hungry to worry about it and sat down to eat. Allan and I managed to stay awake and

talk meteorites around the campfire, drinking whisky, while an inquisitive local boy kept

an eager eye on us. Sometime after going to sleep, I was awakened

|

|

in the middle of the night by what sounded

like a wild animal. I quickly realized that it was Allan snoring loudly two tents away. I

was expecting to see Samburu warriors with their spears at the ready. I heard others

stirring in their

|

|

tents and began to laugh when Chep called out from across the

campsite, “I think somebody got a big head from drinking and snores like the lion.”

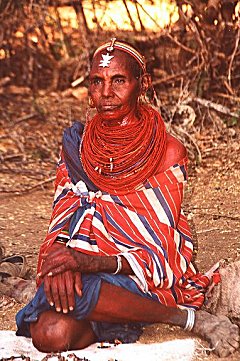

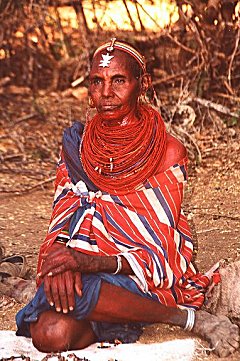

The next morning we awoke to a swap meet-like atmosphere. The women of the tribe had

spread out many blankets with trinkets for us to buy. All we wanted to see were piles

of stones we could search through in hopes of finding some meteorites. We would have

to wait, as there were none to be had this time. After discussing the properties of

meteorites with them and the men of the primitive group, we hoped our next visit would

produce extra terrestrial stones instead of trinkets. Today’s travels would take us

through Masai tribal land and into the Turkana territory, then on to Lake Turkana. It

is known as the Jade Sea because of the turquoise color created by its salty depths.

The going was slow and grueling; comfort was nowhere to be found.

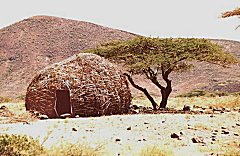

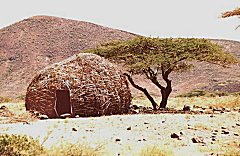

Eventually we made it to our destination, the lakeside village of Loiyangalani. We

entered a fenced compound and were greeted by a fearsome woman named, “Momma”, who

looked like she could put the mightiest of warriors in

their place. We would later witness the “wrath of Momma” when she roughed up one of

the overly eager young male tradesman hanging around. We were then surprised to learn

we would be staying in traditional Turkana reed “banda” huts. The romance of it ended

the second I released the mosquito

|

|

Samburu woman offering trinkets.

|

|

net above the bed. A large amount of bugs and debris

fell over the bedding and me, making me opt not to use the

|

|

Traditional ‘Banda’ hut made of reeds.

|

|

net again. The following day, the terrain changed from volcanic rock to a more sandy ground. To

our astonishment, we came across a basketball court in the middle of the desert! It

turned out that it belonged to a school in a small mission over the next sand dune.

We thought we were beginning to lose our minds from the heat. In late afternoon we

made it to our goal, a mission village named Kalatcha, which borders the Chalbi

desert. We learned that the missionary had lived there for 25 years and had put his

engineering and geology skills to use by building two windmills to pump water and

drive a generator for power.

To our amazement, he had also built a large cement water tank and turned it into a

swimming pool. We enjoyed a late afternoon

|

|

swim in the cool water until sundown.

This was very refreshing from the dust and hot five-day drive we had endured. We

found out from the teachers at the school that it had reached 122 degrees in the shade.

That night, I made my daily phone call and nobody answered at my mother’s house. The

thoughts in my mind ran wild in despair. I didn’t

|

|

know if she was taken to the hospital

or something worse. Thankfully, I had several friends with me for comfort and encouragement.

Unable to reach my family (and the fact that we had finally reached our destination) made

the prospect of sleep impossible.

The first day of searching gave us a renewed energy. Driving from the mission, the low

dunes gave way to flat terrain. Straight in front of us was the vast open desert. When

our guide drove by the occasional stone, one of us would jump out of the truck and test

the hopeful find.

|

|

We made it to the dry lake bed.

|

|

After several hours of “chase and check”, we quickly learned that the

Chalbi was a desert like no other we had searched. Apparently it is a catch basin region

where ancient sediments collected in a huge valley and an underground river from the

distant mountains feeds the area, keeping the soil moist just below the surface. These

|

|

Is it a ‘meteorite’?

|

|

rivers are formed by the yearly “long rains”, when torrential rainfall makes travelling

by land impossible. Any meteorites would quickly be gobbled up when the top layer of the

terrain dried and cracked. Some cracks we saw were up to 18 inches deep. This illustrates

that even with thorough research, unexpected problems occur.

During the last half of the search day, we drove upon what appeared to be a small strewn

field. The stones were slightly magnetic and had what looked like an old crust. We were

elated and took GPS coordinates and several photos. The search continued at an

accelerated rate but came to a quick halt

|

|

when our rig experienced a flat tire. The

journey would test the old military vehicle; as we would have many breakdowns due to

flat tires, broken leaf springs and a host of other expedition delaying occurrences.

When the heat was too unbearable to handle, we headed back to the campsite in the early

afternoon. It was decided that if the next

|

|

day’s search did not produce meteorites, we

would search other possible areas we spotted on the way to the Chalbi Desert.

We spent the rest of the day floating in the pool and chasing water beetles that shared our

refreshing enclosure. April swore at the little creatures swimming around her. Allan

and I laughed every time she screeched in horror whenever one would surface next to her.

Sammy was constantly at her side offering to help in hopes of winning her affection.

The next day we decided to search the southern region and were

|

|

‘Field fixing’ one of many flat tires.

|

|

immediately pleased to see that the terrain was much better. The ground was much more solid and the cracks

were smaller or nonexistent compared to the previous day. April turned on the GPS and

plotted our route for the day. A few hours later she showed us the haphazard path on

the display and Allan exclaimed, “It looks like a bunch of drunken

|

|

The great salt sea, not a good sign!

|

|

sailors!” Another couple of hours and we observed a white haze on the horizon. We thought it was

a mirage but when we came closer we realized the white was a salt layer on the surface

of the soil. It looked like freshly fallen snow, and

eventually we were completely surrounded by the white blanket.

We decided the Chalbi

didn’t want to give up its secret cache of meteorites. The northern side had large

cracks where any meteorites would be devoured by the desert floor and the southern

end had a devastating salt layer that would quickly consume and dissolve any extra

terrestrial material.

Alternate plans were now in effect and we headed back towards camp in the mid-day

|

heat. We met with Father Andesa from the mission regarding educating the locals

about meteorite hunting. He didn’t sound too interested in this but said we should

talk with the chief of the village. He told us about another desert that might be

appealing to us and then about a witnessed fall that fell 14 years earlier near a

town called Marsabit.

I once again used the satellite phone to call regarding my mother’s condition and

got through this time. I was informed that she was back in the hospital and that

she was not doing well. Adam said I should try to get back as soon as possible. I

told him it would take four to five days just to get back to Nairobi, then another

day to get home. Now I was in real need of friends and my expedition members became

a surrogate family to me.

We were unable to make contact with the chief so we departed. The next two days were

spent driving to different villages and educating the locals by telling them to look

for stones that did not “belong” and to save them for us until a later visit. We

stopped in a remote village after an exhausting journey. The next day we headed east

towards Somalia, making our way to the barbarous village of Marsabit. Our armed

escorts would be a comfort here! Mwaura informed us that Marsabit was a Muslim

community and with the current world affairs, we should keep a low profile.

The hotel we were staying in also had a mosque for Muslim travelers. We were all pretty

uneasy because the next day was the deadline set for Saddam Hussein to leave Iraq.

I went to bed and was woken up a few hours later by someone trying to get into my

room. I thought, “Oh no, now I’m in for it!” As it turned out, the guy was drunk

and attempted to unlock the wrong door. The rest of the night, I slept with one eye open.

Without incident, we left early

|

|

the next morning and headed for the Kaitsut Desert,

recommended by Father Andesa, then onto the village of Loglogo, the site of a

witnessed meteorite fall. No sooner did we start our trek when we heard a loud

“clunk” from the front of the Land Rover. One of the front leaf springs had broken.

Mwaura did not have a spare, nor could we replace it even if we did. Having

experienced this problem before, Chep quickly jumped into action and pulled out a

machete. He went into the brush and returned minutes later with a branch and carved

a makeshift splint for the steel leaf spring. He then wrapped strips of an old

inner tube around both parts and then bound the entire “patch” with a length of

heavy twine. The last step for the repair was to soak the whole assembly with

water to make the rope expand and tighten the entire mass.

“...the star that fell from the sky.”

|

|

Chep makes a great ‘MacGyver’. African ‘bush repair’ to broken leaf spring.

|

After several hours of driving we reached the Kaitsut Desert and found that it

consisted of tall grass and scrub brush making for poor meteorite hunting. We

continued to the village of Loglogo, home of the Rendille tribe. We talked to

one elder who said he knew of the “star that fell from the sky.” He said,

“It made a hole like a hyena but it was different because I know the difference!”

He and another tribesman knew the most about the event so they would talk with

the other elders of the village and keep in contact with us through the local

mission. Again, we spent time with them teaching the different characteristics

of meteorites and distributed photos and other material to look for the elusive bounty.

With all of the breakdowns and false leads, this expedition went through Plans

A to D. Now we were on to Plan E - “Escape from the Desert in One Piece!” The

battered vehicle was literally disintegrating beneath us and was starting to

look like something from the “Flintstones”. We were in the worst predicament

we could be in - barely any water remaining, no spare parts and darkness looming.

We would be forced to drive the Trans-East-Africa highway, as it is called, by

night. I think they add the “Trans” part because the harsh road transforms your

vehicle into a pile of broken metal. Our strong Kenyan partners were now showing

signs of stress, which did not help the rest of us.

We stopped in an isolated village and gathered well-needed supplies, continuing

on to the Samburu National Game Reserve where we would stay the night. We were

each assigned an old canvas tent to bunk in. I called Adam and was successful

in getting a connection. He informed me that our mother had slipped into a coma

and to do anything I could to get home quickly. I told him about the Land Rover

falling apart and that we were at its mercy getting back to Nairobi. I hung up

and felt an even greater sense of desperation than before.

Without incident, we left early the

|

|

Alpha baboon shows who’s the boss!

|

|

next morning and headed for the Kaitsut Desert,

recommended by Father Andesa, then onto the village of Loglogo, the site of a

witnessed meteorite fall.

No sooner did we start our trek when we heard a loud

“clunk” from the front of the Land Rover. One of the front leaf springs had broken.

Mwaura did not have a spare, nor could we replace it even if we did. Having

experienced this problem before, Chep quickly jumped into action and pulled out a

machete. He went into the brush and returned minutes later with a branch and carved

a makeshift splint for the steel leaf spring. He then wrapped strips of an old

inner tube around both parts and then bound the entire “patch” with a length of

heavy twine. The last step for the repair was to soak the whole assembly with

water to make the rope expand and tighten the entire mass.

The next morning we awoke to find that Allan’s knife and the beers were missing.

By the way the baboons and monkeys were constantly raiding our campsite, it was

reasoned that a baboon had pilfered the goods. I pointed at the dominant male

and said that it must be the one to blame. The New Yorker then said,

“I’m going to mop the floor with that bastard and show him who the boss is!” He

approached it and was immediately met by a gaping mouth with long fangs and a

blur of flailing appendages. He backed away slowly and

|

said the gangly beast

could keep it because he wasn’t going to mess with an intoxicated primate. He

said he would have to tell his wife he lost it because she would never believe

his story. I said, “That’s fine, but what about my beer?” We laughed and joined

the group at the ailing vehicle.

Travelling over the next three days towards Nairobi was agonizing and exhausting.

We went through several villages and saw many exotic animals including zebra,

giraffe, elephants, ostrich, crocodiles, gazelle and more thieving baboons and

monkeys. Our vehicle managed to get us back and we concluded our business with

our Kenyan partners.

The flights home were long and very emotional for me. I envisioned my mother as

I had last seen her, awake and smiling, wishing me a wonderful trip and to hurry

back. It was comforting to know that Adam and my sisters were there to care for

her in my absence.

Upon landing in New York, I called Adam and learned that our mother had passed

away during the night. Allan offered to stay with me but I did not think he

should since I had a six-hour layover and he had a three-hour drive to get home.

The intent of this pioneering expedition was to promote the hunt for meteorites

in an unknown land and to set up partnerships with the mysterious inhabitants.

We encountered many hardships and a great loss, yet we walked away with a sense

of accomplishment having fulfilled our goals. We feel this is the start of

something special. We were battered and broken, but not beaten, and we have an

even greater desire to find and explore new hunting grounds throughout the world.

This article is dedicated to the loving memory of Bernice M. Hupé, we will miss her dearly.

|

|